Projectile Prediction: Part 1

Part 1 of a series exploring and implementing projectile prediction for multiplayer games. This part breaks down the theory behind projectile prediction, some approaches to implementing it, and a short overview of the version we’ll be implementing, starting in part 2, using Unreal Engine and (optionally) the Gameplay Ability System.

The code used for this series can be found on Unreal Engine’s Learning site.

Introduction

Client-side prediction is a crucial component of making real-time online games feel responsive. It’s commonly used for things like character movement, abilities, and visuals to conceal the effects of latency, and to provide a more fair experience for players with volatile network conditions.

I’m assuming you know how client-side prediction works if you’re reading this. If not, this video provides a good overview of the topic.

One core feature of client-side prediction, present in most modern multiplayer games, is projectile prediction.

Projectile prediction is the client-side prediction performed when a client fires a projectile (a rocket launcher, a grenade, etc.). When the player presses the “fire” input, we want to instantly spawn and simulate the projectile for them, instead of waiting for the server to do it, to keep the game feeling responsive.

For disambiguation, the term “projectile prediction” can also refer to the indicators that appear when players are preparing to throw or shoot something, showing them the trajectory in which their projectile will travel. This is a separate, unrelated topic that we aren’t covering here.

In this series, we’ll examine the theory behind projectile prediction, and walk through a configurable implementation of projectile prediction that mitigates latency and improves responsiveness, without sacrificing fairness:

In this section, we’re looking at some approaches to implementing projectile prediction. In parts 2 and 3, we’ll walk through creating a Gameplay Ability System ability task to predictively spawn projectiles. And in part 4, we’ll look at an implementation of a base projectile actor class, breaking down its features and reconciliation techniques (since a step-by-step coding walkthrough wouldn’t be practical, given the length of the code for that class).

Possible Approaches

Unfortunately, projectile prediction ends up being a lot more complex than predicting simple actions (like ray-tracing a gunshot or triggering a particle effect): projectiles are tangible actors; they may have complex hit detection, physics simulations, and a myriad of potential side effects that can be triggered during their lifespan (like an explosion when landing). If we were to simply spawn the client’s version of the projectile instantly, we would quickly discover synchronization issues and visual discrepancies (which we’ll see later on).

Like most things in game development, there’s no universal solution to this problem. Different games implement client-side prediction in a different way, specifically suited to the needs of the project. So let’s start by looking at some possible approaches.

No Prediction

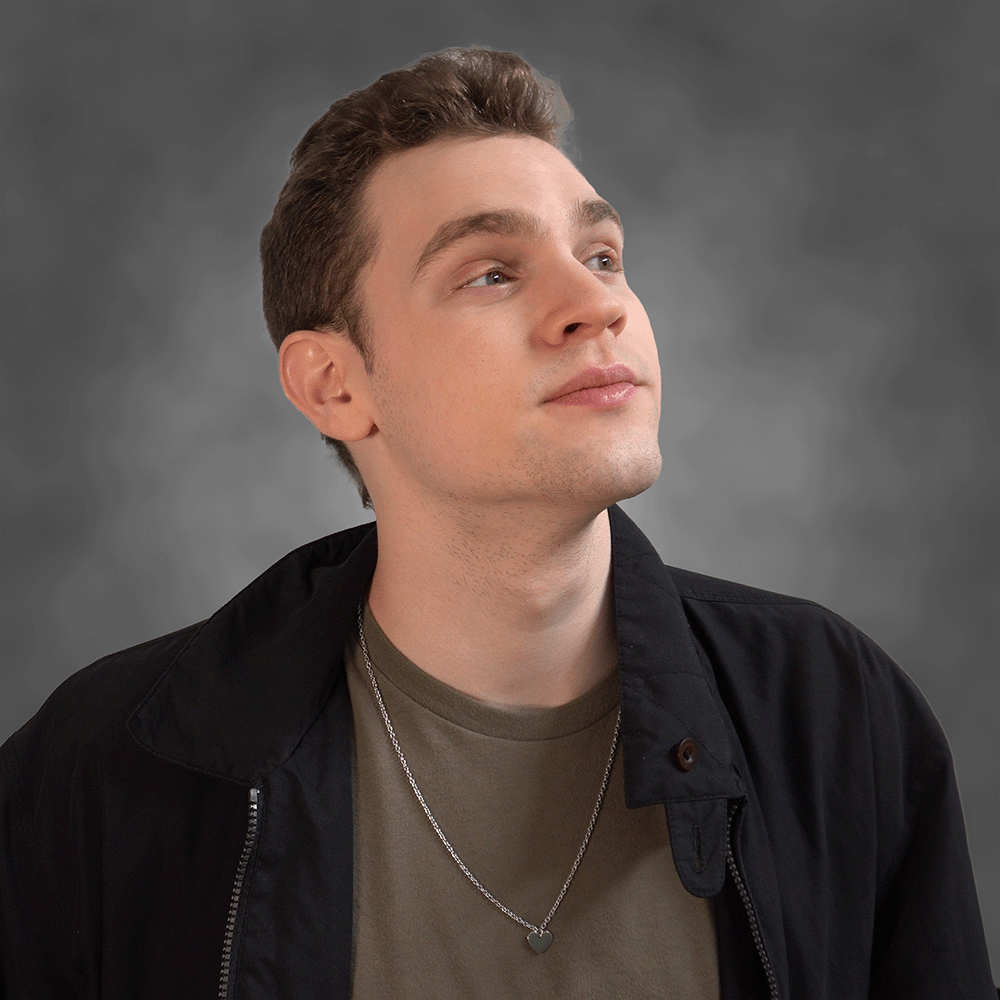

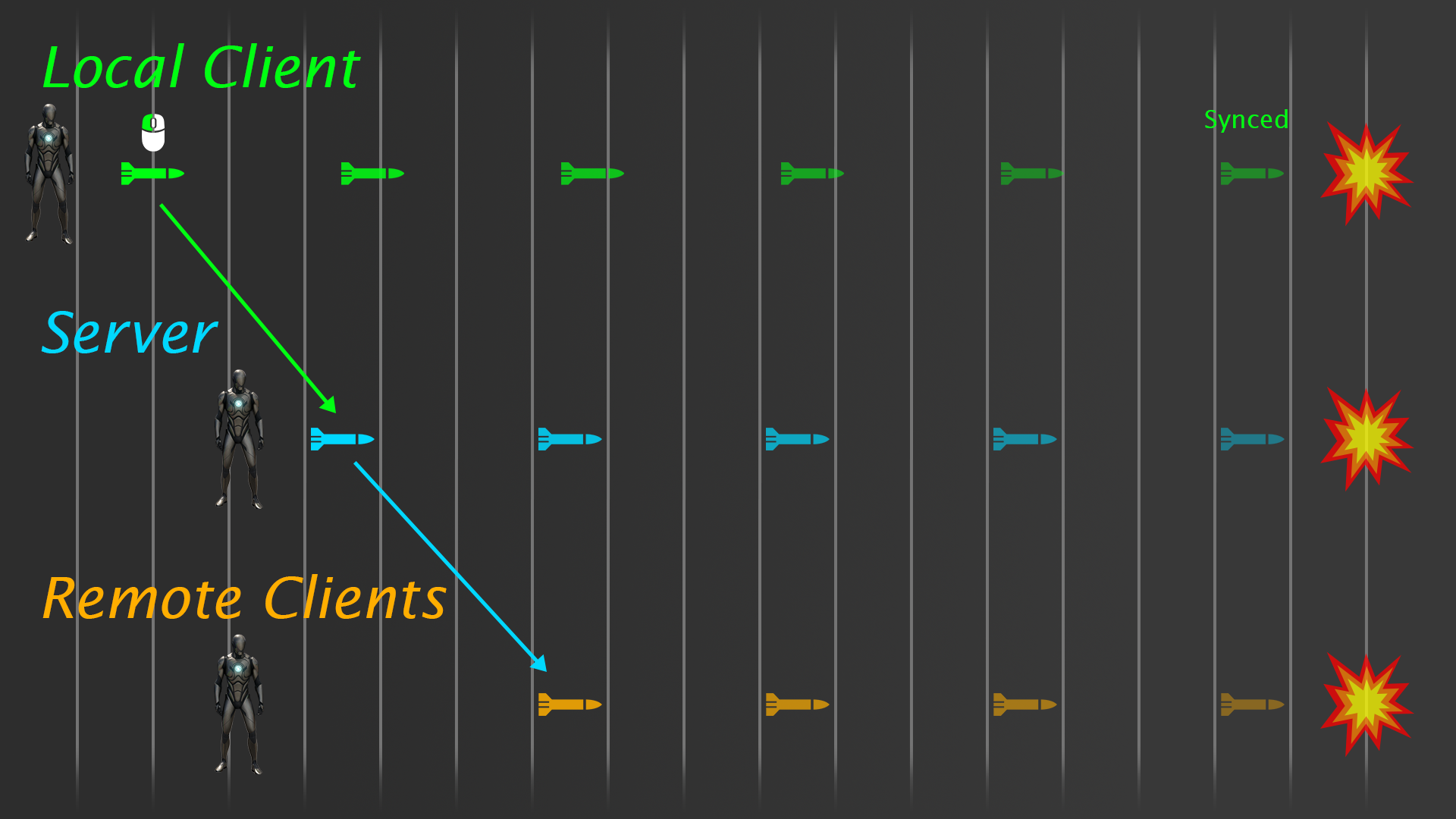

Just to get a baseline, let’s look at what our projectile would look like without any prediction at all.

In this situation, when the player presses the “fire” button, they send a message to the server, asking it to spawn the projectile. Once the projectile is spawned on the server, it’s replicated back to clients.

In this diagram, the distance between the mannequin and the first projectile represents where the projectile appears locally, relative to its actual spawn location. On the server, the projectile appears at its proper location, right in front of the player, as soon as it’s spawned. But because it takes time to replicate the projectile back to clients, the projectile will appear ahead of its spawn location, since it’s been traveling in the time it takes to replicate (the exact distance will be \(({client \: ping} / 2) \cdot {projectile \: velocity}\)).

Already, we can see two big problems. First: the projectile is spawned a considerable amount of time after the player presses the input, since it takes time for the input request to reach the server. For clients playing with 60ms of ping (round-trip time), it will take 30ms for a projectile to spawn on the server, and another 30ms for that projectile to appear on the client. Second: projectiles appear a noticeable distance ahead of where they’re supposed to be, on both the local and remote clients. If a projectile is traveling at 100m/s, it will appear 3m ahead of where it should on clients with 60ms of ping.

When I say “local” and “remote,” I’m referring to the perspective of the projectile, not the server. So the “local client” is the client that fired and owns the projectile, while the “remote clients” are any of the other clients connected to the server.

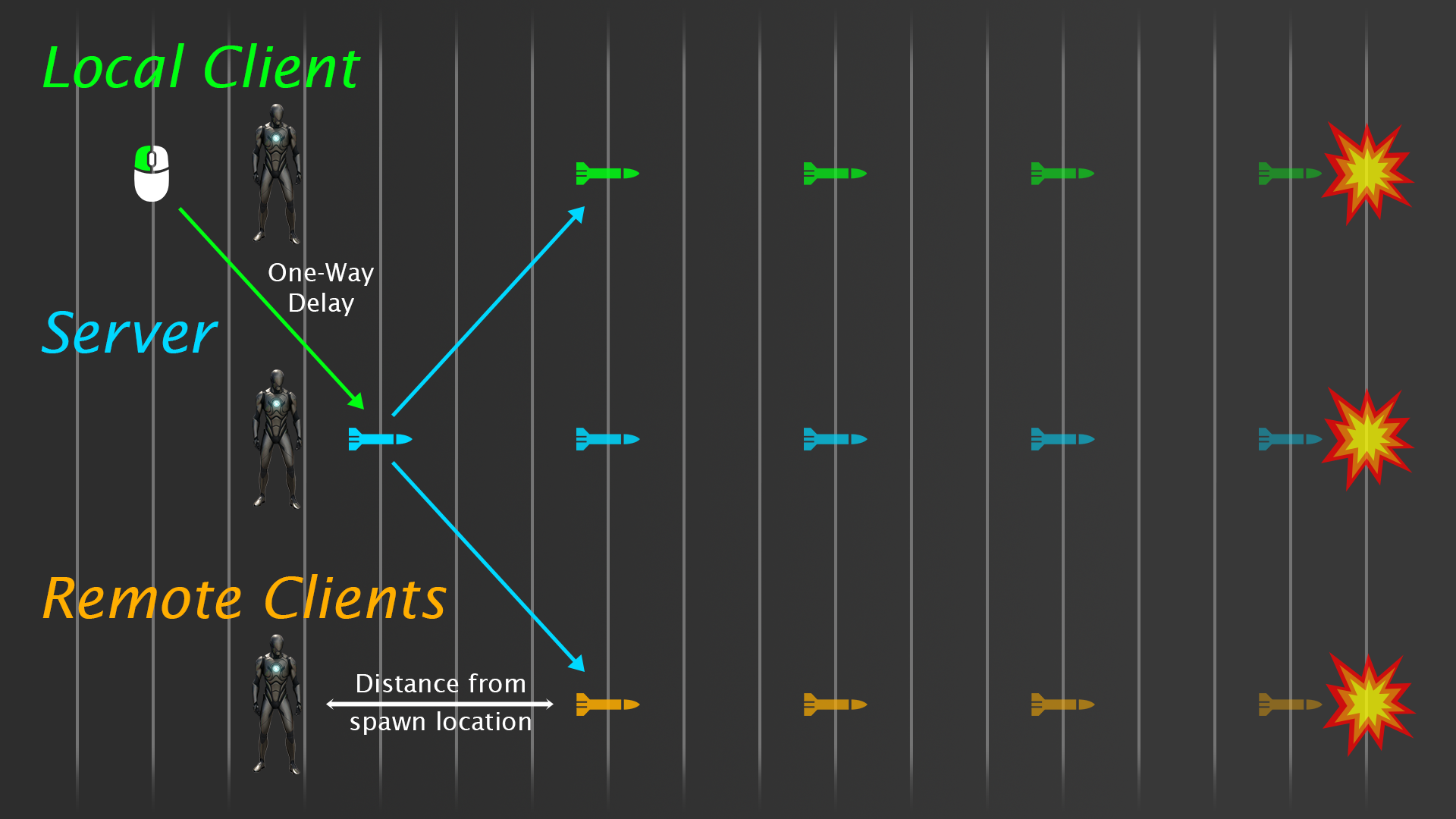

Fake Projectile

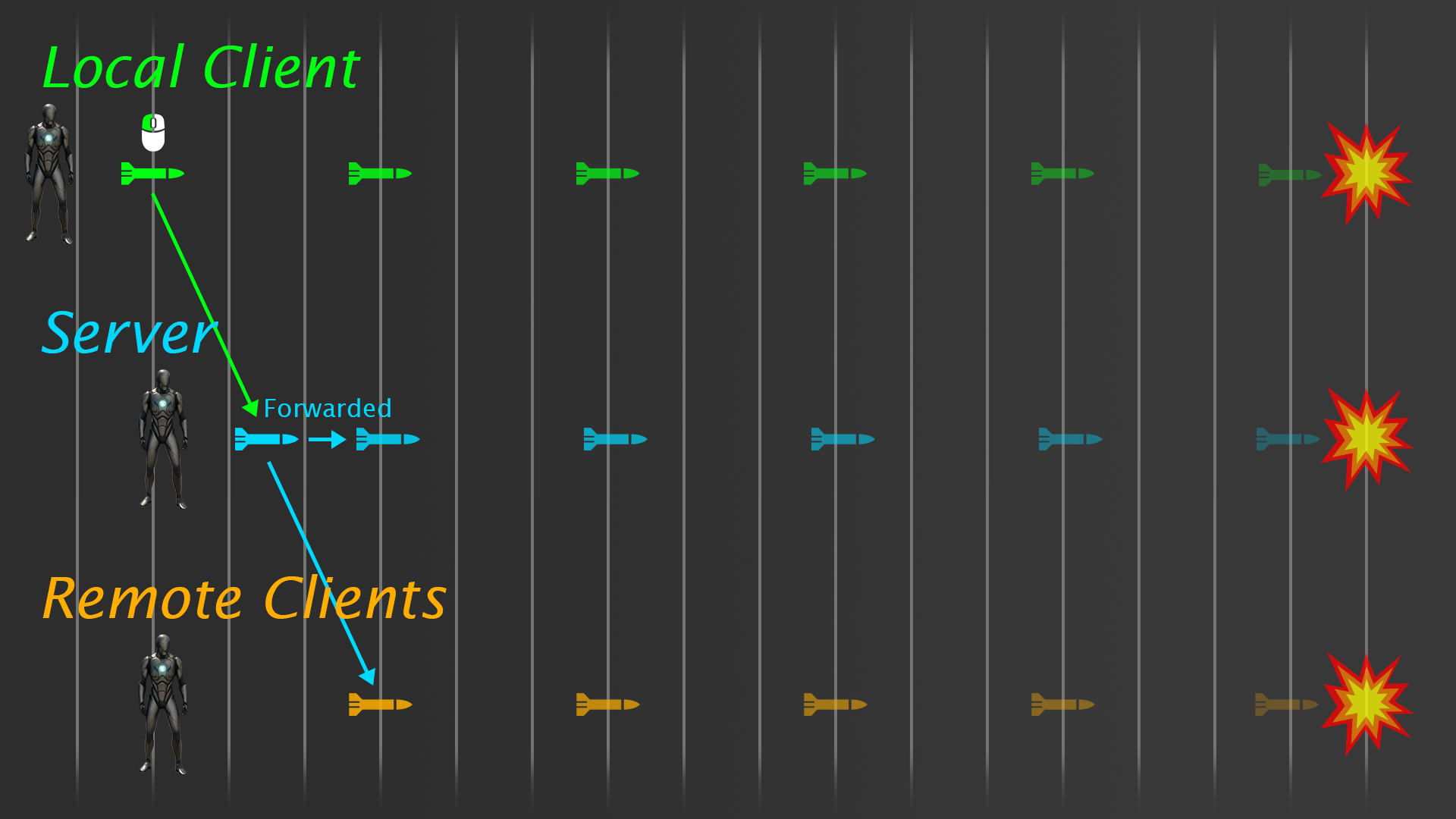

To solve these problems, a good place to start is the conventional client-side prediction method: performing the action instantly locally, and reconciling later on if necessary. To do this, when we press our input, we can spawn a “fake” projectile locally that instantly starts traveling.

This presents a new issue, however: because we’re spawning the fake projectile before the real projectile, it will now be ahead of it. This desynchronization can result in jarring visual discrepancies: the client’s fake projectile will hit its target before the real projectile does, or it may hit something that the real projectile missed, or vice versa.

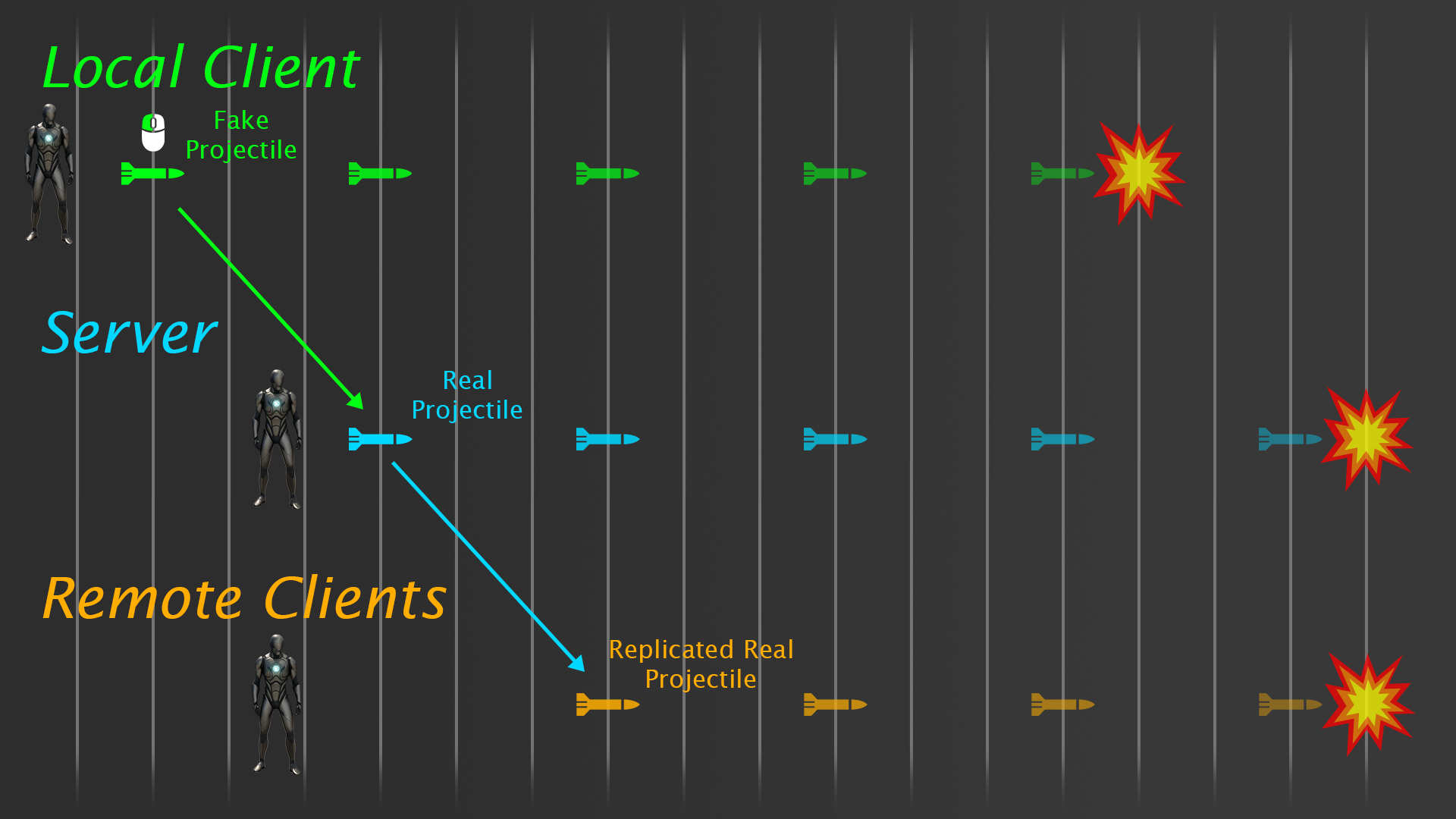

Fake Projectile with Synchronization

To fix our synchronization issues, after spawning the fake projectile, we could try to synchronize it with the real one once it’s been replicated. There are actually two different ways to implement this particular solution.

The first solution is to simply teleport the fake projectile to the real projectile’s location once it’s replicated.

This is how Unreal Tournament handles projectile prediction. You can see how they implement it here.

The downside of this is that the projectile will visibly “jump” backwards in time, since we’re switching between projectiles that are in two different locations. However, projectiles are usually so small and travel at such high speeds that this jump isn’t noticeable—especially amidst the action of a fast-paced game.

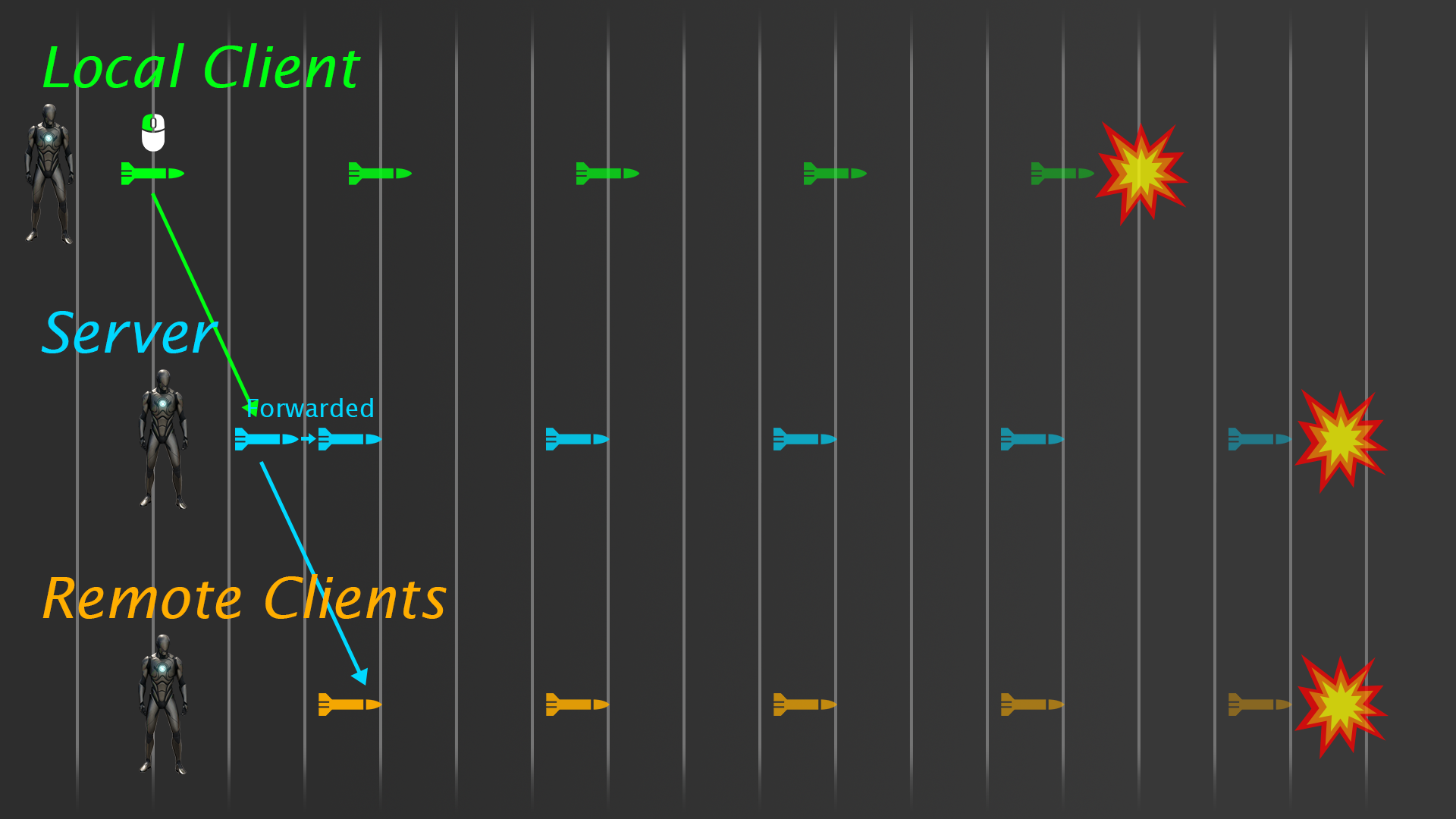

An alternative solution is to smoothly synchronize the projectiles over time by lerping the fake projectile towards the real one.

This creates a smoother visual, but if the projectile hits something shortly after being fired, it may not have had enough time to fully synchronize yet. Though, in practice, it’s highly likely that both the fake and real projectile will end up hitting that same target in this situation, even if they haven’t fully synchronized yet.

Both of these solutions are perfectly viable (our implementation will use the latter), and they help solve both of our problems (at least, for the local client; we’ll get to fixing remote clients later). However, there’s another major issue that might be difficult to notice just from these diagrams, and it has to do with both responsiveness and fairness.

We mentioned that our predicted projectile is a “fake”: it doesn’t actually damage enemies or have any effect on gameplay; that’s still the responsibility of the server’s projectile.

What that means is that, since the server’s projectile is the one actually performing hit detection, players with lower latency will still have an advantage, because their projectiles will be spawned on the server faster and be closer to their desired shot. This is another issue that we may want to account for.

Fast-Forwarding

Ideally, for maximum responsiveness and fairness, the real projectile should be as accurate to the fake projectile as possible, since the fake projectile represents what the client actually wanted to fire. To do this, we can “fast-forward” (a.k.a. “forward-predict”) the server’s projectile, so that it appears where it would be if it had been fired instantly by the client.

This—combined with our fake projectile—essentially mitigates latency from the equation completely, which is great. However, you might realize that this presents yet another problem: fairness for other players. If a client is playing with 200ms of ping, on the server, their 100m/s projectile will be fast-forwarded 10m ahead of where it spawned, and, on other clients, will appear 20m ahead of where it spawned. That means that if a player is any less than 20m away (a pretty massive distance), they’ll never even see the projectile, because it will hit them before it even appears on their screen.

In addition to being visually jarring, this just isn’t fair to other players.

Partial Fast-Forwarding

To help keep things fair, instead of completely fast-forwarding the projectile to where it should be on the client, we can instead fast-forward it only partially. By measuring the client’s latency, we can fast-forward it just enough such that it appears somewhere between where the local client “wants” it (e.g. some 10m ahead), and where the server “wants” it (right in front of the player).

Placing the projectile closer to where the local client wants it favors the player; placing it closer to where the server wants it favors other players. So, for a good compromise, we could place it about halfway between where the client and server want it (which, granted, this diagram doesn’t do a great job at showing):

To prevent the projectile from ever fast-forwarding an extreme distance, we should also place a limit on how far we can forward-predict the projectile.

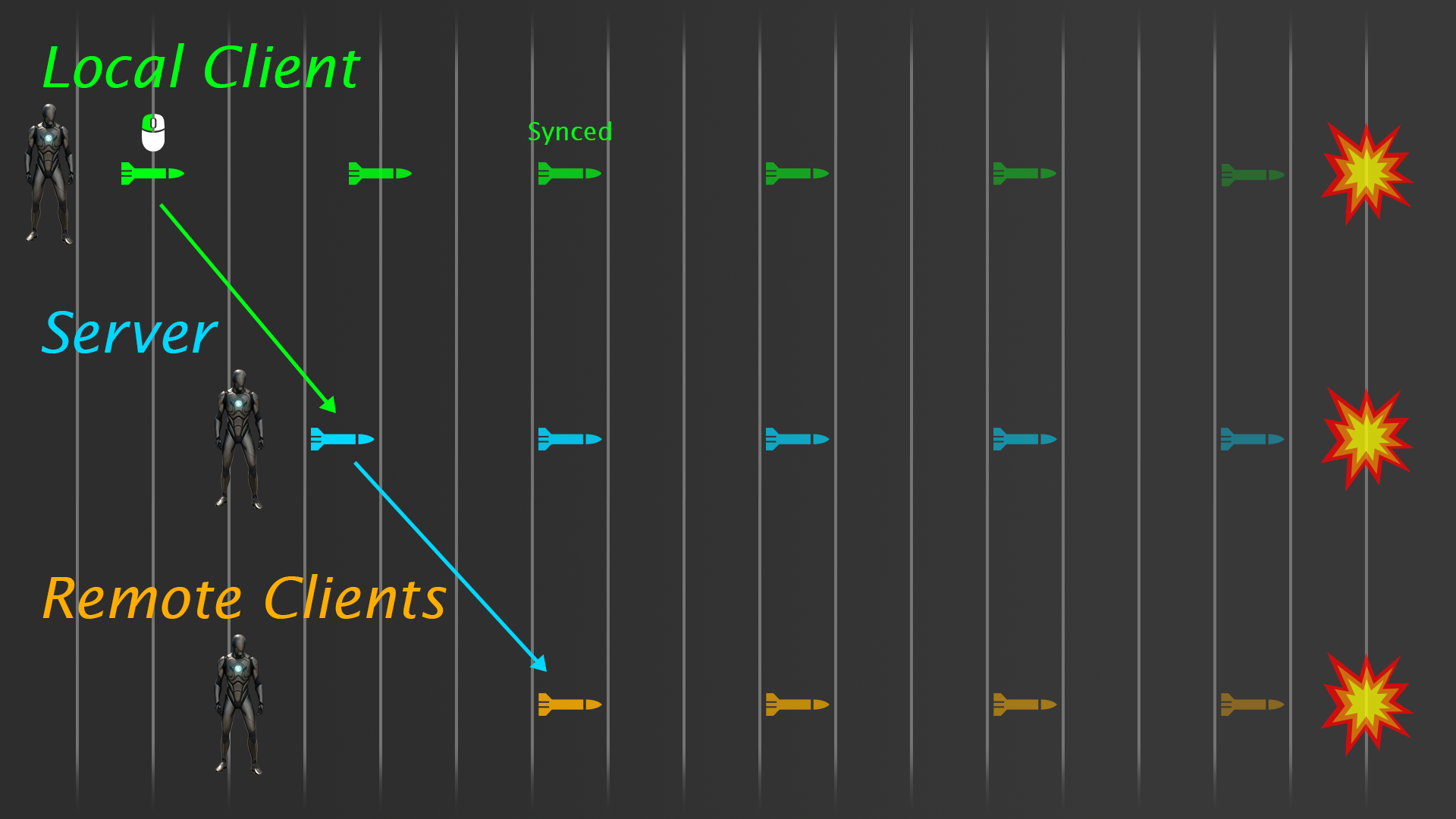

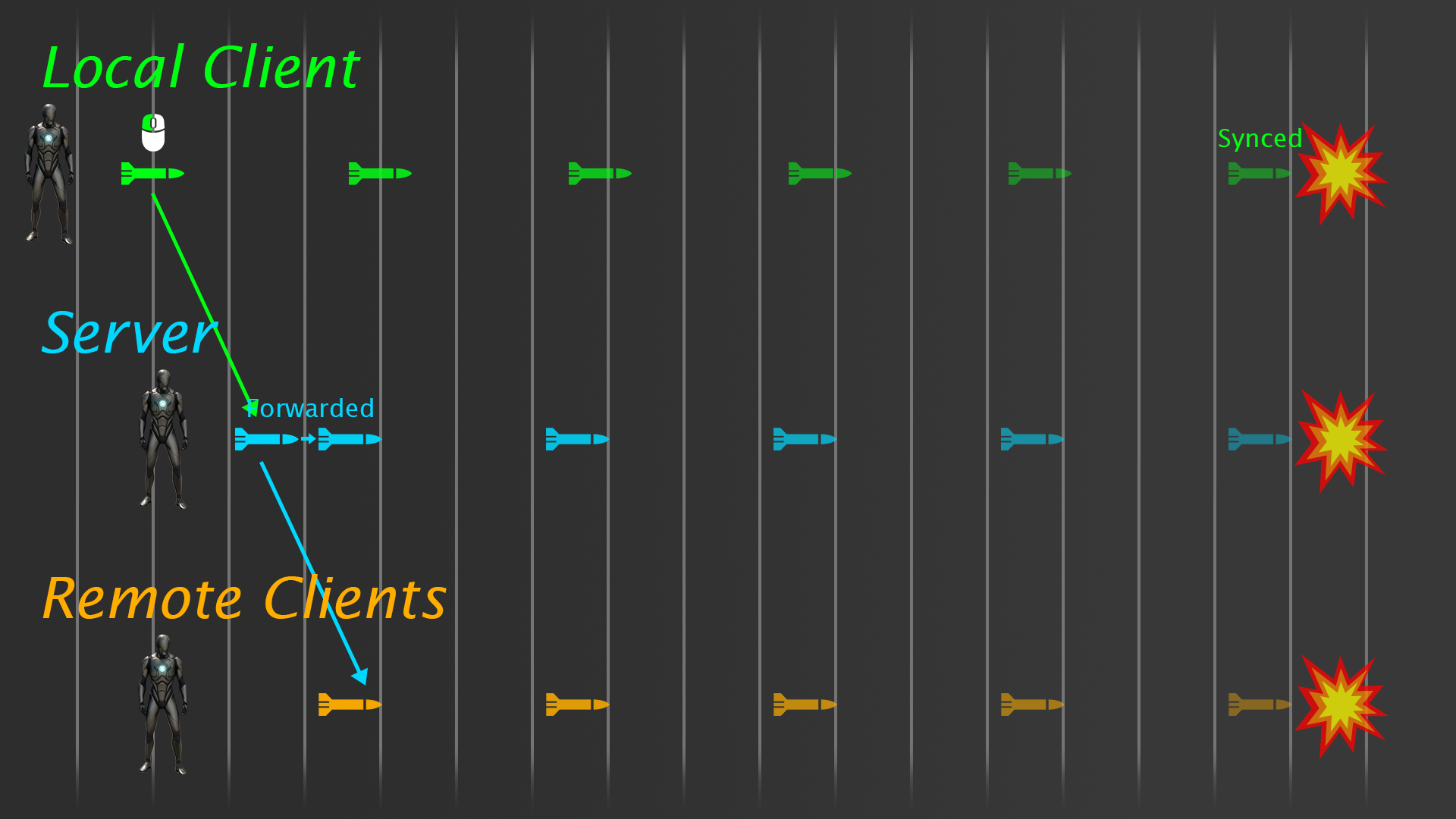

Partial Fast-Forwarding with Synchronization

Since we’re only partially fast-forwarding the projectile now, it won’t appear exactly where the fake projectile is anymore. We can bring back our synchronization techniques to make sure both projectiles look the same.

Now, our projectiles look good and feel fair on both the server and the local client, but they still look bad on remote clients due to replication time and forward-prediction. So how can we fix this?

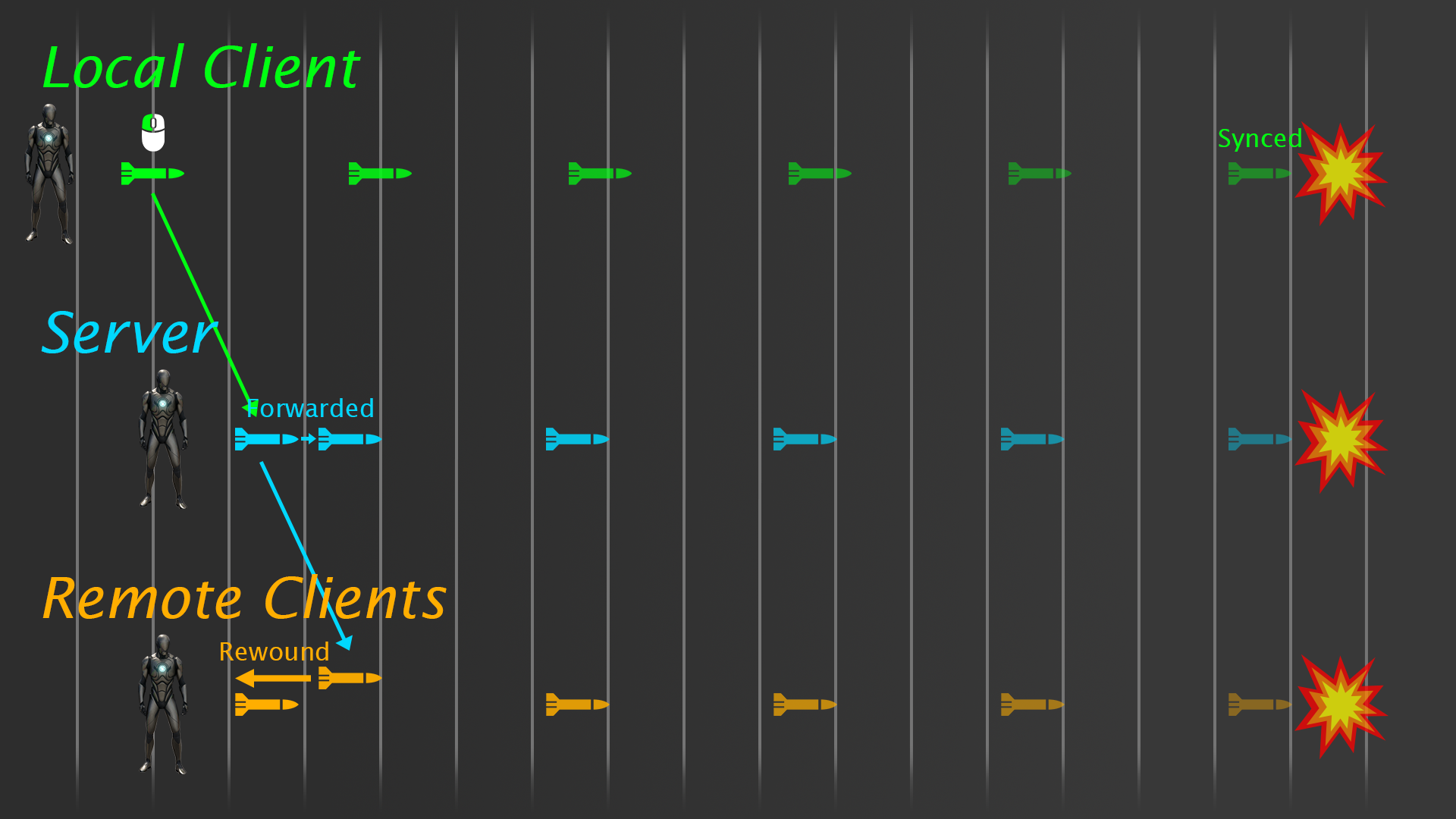

Partial Fast-Forwarding with Synchronization and Resimulation

To make projectiles look good on remote clients too, we can resimulate them locally.

When the projectile is initially replicated to a remote client, we can rewind it, back to its spawn location, then replay its trajectory, allowing remote clients to see the projectile’s entire lifespan, from start to finish.

You might think that this will cause synchronization issues, since the remote client’s projectile is now behind the real one. However, in practice, this isn’t really the case. Because of replication time, the projectile will already be behind. For example, if we trigger some explosion VFX with an RPC when the server’s projectile hits something, it will take 30ms (assuming 60ms of ping) for that explosion to appear on remote clients. When that 30ms ends, our projectile will likely have already caught up to where it exploded on the server.

Solution

Each of these approaches is a decent model for a projectile prediction system. Some are better than others, but they all have pros and cons, and you can probably find examples of each in various games.

In the subsequent parts of this series, we’ll walk through and examine the implementation of our own projectile prediction system using Unreal Engine and the Gameplay Ability System, originally created for the game Cloud Crashers. This solution uses the latter of the above models: Partial Fast-Forwarding with Synchronization and Resimulation, but it’s highly configurable, and should be well-suited for a wide range of projects. And, of course, you can modify it to your needs.

We only use the Gameplay Ability System so we can hook into its prediction system to spawn our projectiles. If your project doesn’t use GAS, you can still use this code; you’ll just have to spawn the projectiles your own way.

Before we dive in, let’s look at an overview of how this system will work, and recap how our prediction model will operate.

Spawning

To spawn our projectiles, we’ll use the Gameplay Ability System to predictively spawn a “fake” projectile on the local client, spawn the real projectile on the server, and link the two together so they can be synchronized. The next two sections of this series consist of a step-by-step walkthrough to implementing this code.

We’re using GAS so we can hook into its built-in prediction system. We’ll spawn projectiles inside gameplay abilities so that if our ability is rejected by the server, we can reconcile the missed prediction by destroying our fake projectile. We’ll handle other prediction logic on our own; we’re just using GAS to predict the actual spawning of the projectile.

If you have a game complex enough to necessitate projectile prediction, you should seriously consider using GAS as your gameplay framework.

Initialization

On the server, when our real projectile is spawned, it will be forward-predicted to about halfway between where it was spawned on the server and where it would be on the client that fired it (i.e. halfway between where it spawned and where the fake projectile currently is).

On remote clients, when the real projectile is replicated, it will be rewound to its spawn location and resimulated.

Projectile Logic

All projectiles will derive from a base Projectile actor class. This class will use a projectile movement component for its physics simulation, and use two different collision shapes for hit detection: one to detect hits against the environment, and one to detect hits against targets (e.g. enemy players).

It’s important to note that projectile movement is not going to be replicated, because projectile movement replication tends to look horrible, even at high net update frequencies. Instead, each machine will simulate the projectile’s movement locally, which is why our reconciliation is so important: we have to make sure that each projectile spawns, travels, and lands the exact same way.

Our base projectile class will be highly configurable. It will have various configurable properties to control how the projectile is predicted (e.g. whether the fake projectile should predict visual effects, or if it should wait for the real projectile’s effects), in addition to how the projectile appears and moves. It will also have configurable VFX, SFX, force feedback, and decals that can be triggered predictively or authoritatively.

Synchronization & Reconciliation

As the projectiles travel, they’ll be synchronized and reconciled to ensure that their local simulation always looks and behaves the same on all machines.

On the local client, once the real projectile is replicated from the server, the fake projectile will be lerped towards it over time until both projectiles are synchronized.

When any projectile hits a terminal event (i.e. hitting a target, which triggers its destruction), several reconciliation techniques will be used to ensure that that event occurs the exact same way across all machines. E.g. if the fake projectile hits something that the real projectile missed, we’ll ignore the hit, and keep simulating until the real projectile hits something; if the real projectile hits something that the fake projectile missed, the fake projectile will jump to where the real projectile landed; etc.

What’s Next?

Now that we understand our desired model for projectile prediction and have an overview of how we’ll implement it, let’s start by implementing the gameplay ability task that handles spawning the fake and real projectiles.