Projectile Prediction: Part 4

The fourth and final section of a series exploring and implementing projectile prediction for multiplayer games. This part breaks down the implementation of a base Projectile actor class, which can be subclassed into projectiles that can be spawned by our SpawnPredictedProjectile task.

The code used for this series can be found on Unreal Engine’s Learning site. Additionally, a more concise explanation of this code can be found at the official documentation page.

Introduction

In the last section, we walked through the “linking” step of initializing projectiles. In this section, we’re breaking down how we implement a base Projectile class for Cloud Crashers (which we spawn using the SpawnPredictedProjectile ability task we created earlier in this series). We’re going to go through all of this class’s key features, prediction methods, and reconciliation techniques, providing an explanation of how everything works and the reasoning behind it.

Fast-Forwarding

In part 1, we decided that we would (partially) fast-forward the authoritative projectile such that it spawns closer to where the owning client wants it.

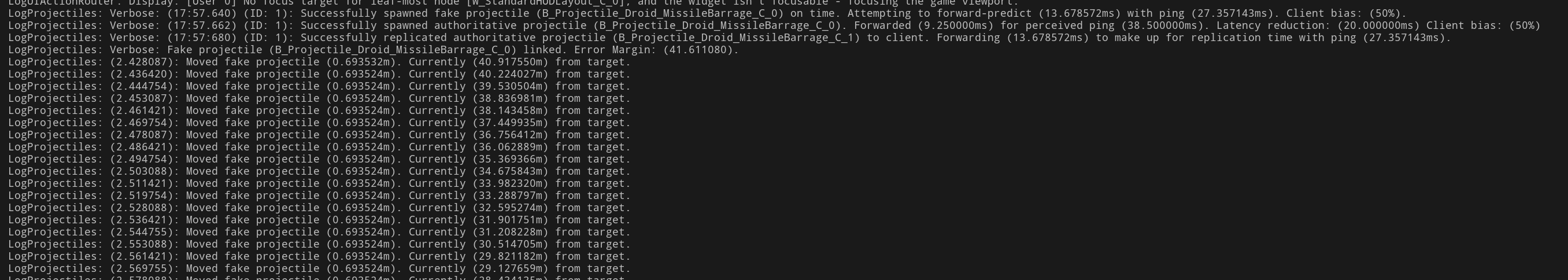

In the SpawnPredictedProjectile class, we fast-forward the projectile in OnSpawnDataReplicated, after it’s spawned, by the ForwardPredictionTime given to us by our player controller. We call TickActor to tick the actor’s components (for things like animations or VFX), and TickComponent on the projectile’s ProjectileMovement component (which we’ll look at in the Movement section) to actually move it forward.

We also call SetLifeSpan to reduce the projectile’s lifespan by the amount it was forwarded in time. All projectiles should have a default InitialLifeSpan set, just to ensure we don’t end up with lingering actors wasting resources if they don’t hit anything.

We implemented this when we created the SpawnPredictedProjectile class, even though we didn’t have a ProjectileMovement component to tick. If you use this code for your projectile, those errors we had will go away. If you choose to implement this class on your own, you can just take that fast-forwarding code out; it won’t break anything.

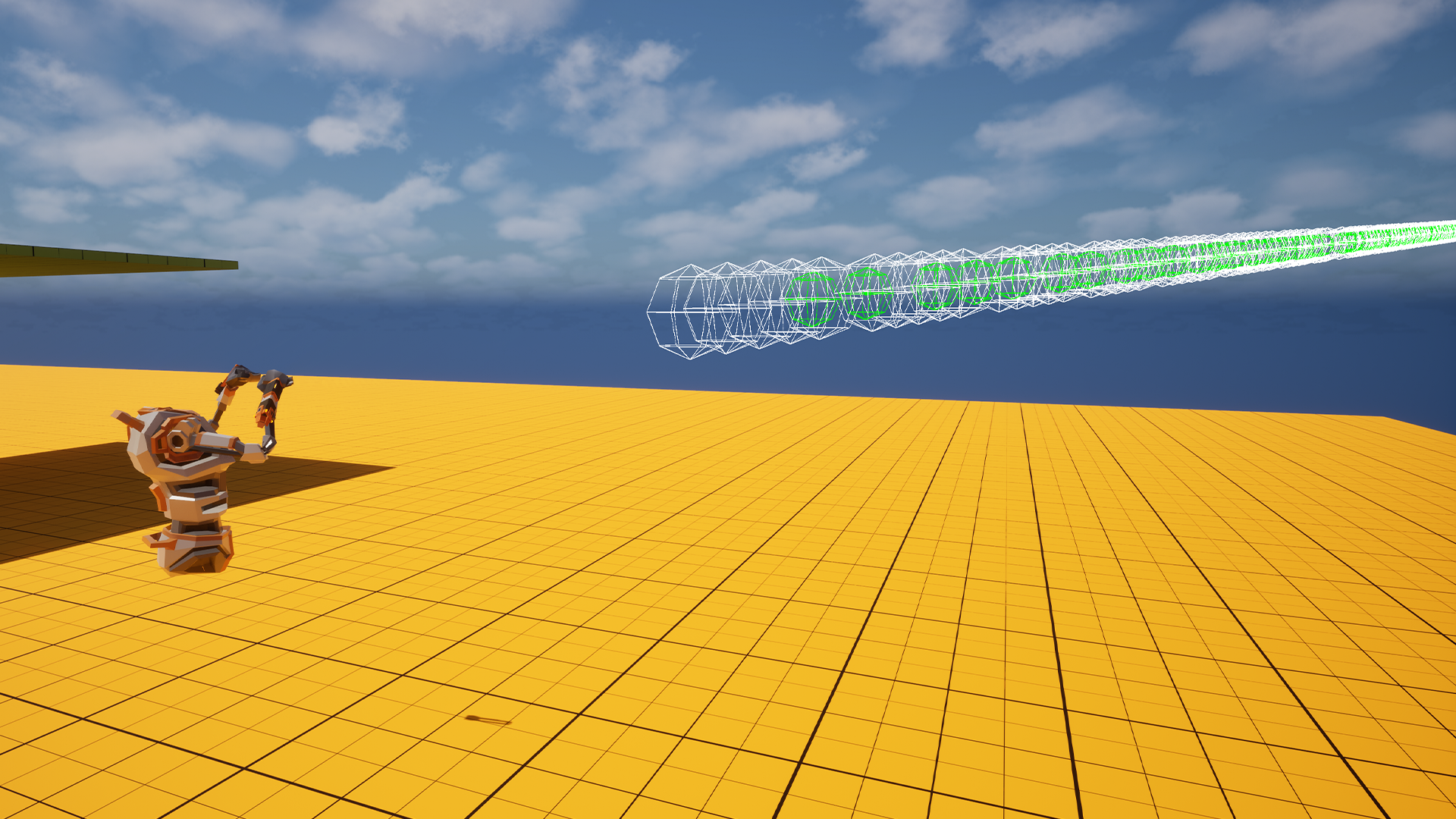

Forwarding the projectile like this can sometimes cause issues with hit detection. Since we’re essentially teleporting the projectile forward in time, if the projectile should have hit something close to its spawn location, there’s a chance it will be teleported right through it, missing it entirely:

To fix this, we need to enable bForceSubStepping on our ProjectileMovement component, decrease MaxSimulationTimeStep, and increase MaxSimulationIterations. This forces the projectile to break its movement into discrete steps, so hit detection can still be performed while forwarding it.

With this, we can still fast-forward the authoritative projectile on spawn, without the risk of missing collisions:

Synchronization

Since we’re only partially fast-forwarding our projectile (again, see part 1), the predicted/”fake” projectile will still not be synced with the authoritative projectile.

We’ll talk more about why this desynchronization can cause issues in the Reconciliation section.

To synchronize our projectiles, we slowly lerp the fake projectile towards the authoritative one. We do this by calling CorrectionLerpTick each tick, which sets the fake projectile’s location one step towards the authoritative one. To actually move the actor, we hack into the ReplicatedMovement property, which can safely handle the movement update (so we don’t have to worry about things like missing collisions).

The rate at which we lerp the projectile is 0.05% of the projectile’s initial speed each tick. This is an arbitrary value that I’ve found to be big enough to synchronize the projectiles quickly, but small enough to be completely unnoticeable to clients.

The replicated authoritative projectile is hidden for the owning client (since we don’t want to see two different projectiles). But if we unhide it, we can see how, once the authoritative projectile is spawned and forwarded, the projectiles synchronize over time:

Debugging

Given the complex nature of projectile prediction, we’ve implemented a variety of options to help with debugging, in addition to extensive logging. These options are defined in a UDeveloperSettingsBackedByCVars class called UGASDeveloperSettings. (Cloud Crashers has a few different developer settings categories. We put our projectile settings in this one because, technically, this projectile implementation is part of the Gameplay Ability System).

These settings allow for the configuration of a variety of debugging options…

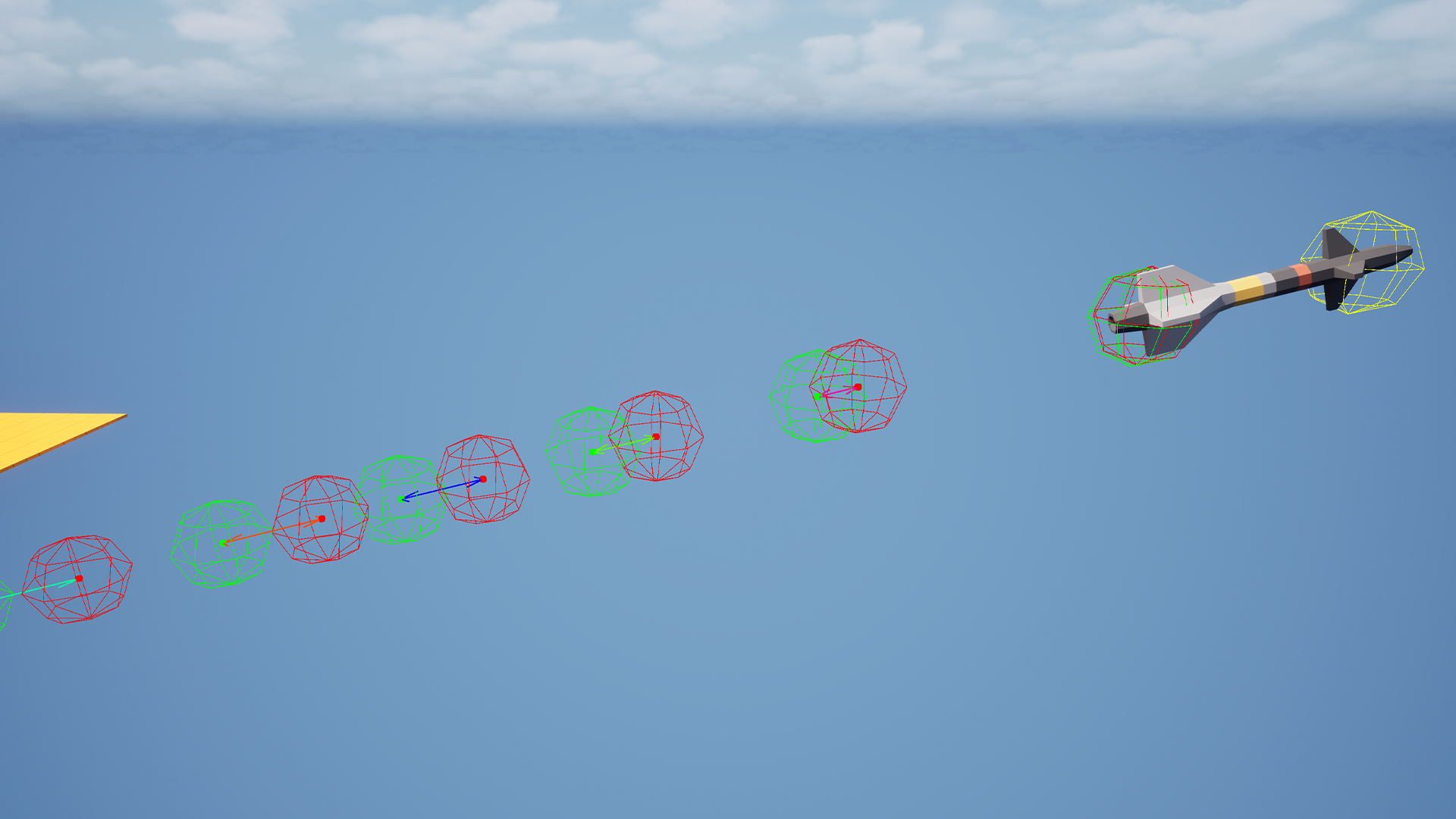

ProjectileDebugMode will draw the position of projectiles at regular timestamps throughout their trajectory. Depending on the setting, we can filter which types of projectiles are drawn:

PredictedVersusClient: Draws the trajectory of the fake projectile and the owning client’s version of the authoritative projectile (i.e. where the authoritative projectile would appear for the client that fired the projectile, if it were not hidden). This is especially helpful for debugging projectile synchronization.ClientVersusServer: Draws the trajectory of the owning client’s version of the authoritative projectile and the server’s version of the authoritative projectile (i.e. where the authoritative projectile actually is).All: Draws the fake projectile, the owning client’s version of the authoritative projectile, and the server’s version of the authoritative projectile.

When making PredictedVersusClient draws, we also draw arrows between the projectiles’ corresponding time steps, to show the difference in their positions at each point in their trajectory. When we sync the projectiles over time, we can see this distance become smaller and smaller, until the two are eventually synced, indicated by a change in color:

And if bWaitForLinkage is enabled, we won’t start drawing until the fake and authoritative projectiles have been linked. If it’s disabled, we’ll always see a few unlinked fake projectile draws, since the fake projectile is always spawned earlier:

bDrawSpawnPosition and bDrawFinalPosition help us debug projectile spawns and hits, by showing the starting and ending position of each projectile, color-coded to each machine:

The “spawn position” draw doesn’t really represent the “spawn” location of the projectile; it actually shows the location of the projectile at the time when it first appeared on a given machine.

In this image, the first white sphere shows where the projectile was spawned on the server (we’re placing it a little bit ahead of the player’s camera, so it doesn’t clip into their viewport). There’s also a red sphere here, showing where the fake projectile was spawned, but it’s in the exact same position as where the authoritative projectile spawned, so the white sphere is hiding it.

Lastly, the first green sphere shows where the authoritative projectile was when it was first replicated back to the local client, which is later due to latency. As the local client, we don’t care about this visual discrepancy, since we don’t actually see the authoritative projectile (we only see the fake one), but we do have to account for this for clients without a fake projectile (i.e. the clients that didn’t fire this projectile), which we’ll look at in the Remote Clients section.

When debugging projectile synchronization, we can log each lerp step performed by enabling bLogCorrection:

Lastly, we can adjust the frequency, duration, and color of each draw with the remaining Draw and Color settings:

Movement

To move the projectile, we use Unreal’s built-in UProjectileMovementComponent class. We don’t use the built-in movement replication solution, however, since it usually looks pretty terrible, even at high net update frequencies.

Instead, we simulate the projectile’s movement on each machine locally. Since we guarantee that both of our projectiles (fake and authoritative) have the exact same spawn location and rotation, they’ll always follow the exact same trajectory.

The only time their trajectories may differ is if one hits a surface that the other misses. We’ll examine how this, and other missed predictions and desynchronizations, can happen in more detail in the Reconciliation section. What’s important regarding projectile movement, however, is that when the authoritative projectile hits something, we enable movement replication, so each projectile will be teleported to the same location to land or explode. Since projectiles are usually destroyed when they land (e.g. rockets are usually destroyed and play an “explosion” particle effect), this is primarily to ensure that any “land” or “explosion” effects occur in the correct location.

To perform this movement replication, we use a variable called ReplicatedProjectileMovement of custom type FRepProjectileMovement, which is an optimized version of the FRepMovement type used by the built-in ReplicatedMovement variable.

We override AActor’s replication functions—PreReplication, GatherCurrentMovement, etc.—to replace ReplicatedMovement with our ReplicatedProjectileMovement variable, and to use our custom bReplicateProjectileMovement variable instead of bReplicateMovement.

When projectiles land, we enable bReplicateProjectileMovement to replicate their final position, to ensure every projectile lands in the same place on every machine:

Using a custom movement replication variable may seem like a wild micro-optimization (which, yeah, it is), but there are a few other changes we want to make to the built-in movement replication code which are made easier by this. For example, we ignore the movement replication on non-owning simulated proxies (the clients that didn’t fire the projectile), since their projectile will be intentionally behind due to being rewound (which we’ll look at in the Rewinding section).

Hit Detection

For hit detection, we use two different colliders: a Collision collider and a Hitbox collider. The former is used to detect hits against the environment, and the latter is used to detect hits against enemies, allies (e.g. for healing projectiles), and other damageable actors (like destructibles).

This allows us to define two different hitboxes for each projectile, which is extremely useful. For example, if we have a “spear” projectile, we’d want it to have a very small hitbox against the environment, accurate to its size, so players can throw it through small gaps. But we might want it to have a more generous hitbox against enemies, so it isn’t difficult to use:

We use the Collision collider as the projectile movement component’s UpdatedComponent, since it’s usually accurate to what the projectile’s actual physics body would be, meaning it also has to be the projectile actor’s root component (just because of how the projectile movement component works). This does, unfortunately, lead to some restrictions on how projectiles can be configured, but I find this setup to be the most flexible without complicating code or requiring multiple base classes.

Detonation

The single most important event of a projectile’s lifetime is its “detonation.” This event occurs when a projectile impacts a valid target, or when it stops moving (because it hit a wall, was stopped by friction, ran out of bounces, etc.), at which point it will typically apply its gameplay effects, trigger any desired FX, and destroy itself.

When a projectile hits a valid target (how “valid” targets are determined is detailed in Effects), we call this a “direct impact” or a “successful hit.” This is triggered by the Hitbox collider overlapping an actor that passes the “valid target” check.

When a projectile stops moving without having hit a valid target, this is called a “missed impact,” and this occurs when the movement component’s OnStop event is invoked. This event can be triggered by the Collision collider hitting a (non-target) blocking surface (since this collider is the movement component’s UpdatedComponent), a bouncing projectile running out of bounces or reaching its StopSimulatingThreshold (due to friction), etc.

Both a direct impact and a missed impact will cause the projectile to “detonate.”

As the projectile’s most important event, it’s crucial that this is synchronized across all machines. All the methods used to ensure this synchronization and to handle missed predictions are detailed in the Reconciliation section.

Effects

Gameplay Effects

Projectiles can be configured to deal direct impact damage, AOE damage, or both. When a projectile detonates from a direct impact, the actor that was hit is referred to as the “direct target,” as opposed to an “AOE target.”

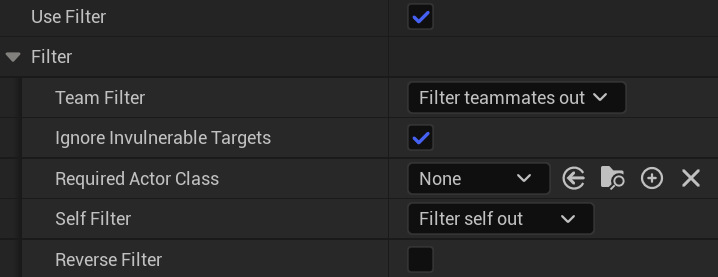

A “direct impact” detonation is only triggered when hitting a valid target. To define what a “valid target” actually is, we use our colliders’ collision settings (e.g. configuring the Hitbox collider to only detect pawns) and a Filter property.

Filter is a variable of type FCrashTargetDataFilter, which is our project-specific FGameplayTargetDataFilter. This variable can be configured by projectiles to define whether an actor should be hit by the projectile depending on its team, its gameplay tags (e.g. actors with an Invulnerable tag are usually ignored), whether it’s the owning actor (e.g. if we want to allow self-damage), whether it has an ability system component, and other parameters:

When the Hitbox collider overlaps an actor, the projectile will only detonate if that actor passes this filter (though this can be disabled with bUseFilter). This filter is also used when determining whether to apply AOE effects to nearby actors.

When a projectile detonates (either because it hit a valid target or because it landed against a surface and can’t bounce), the ImpactGameplayEffect is applied to the target it hit (if there was one), using an enumerator called ImpactEffectDirection to determine the direction of the effect (e.g. for knockback).

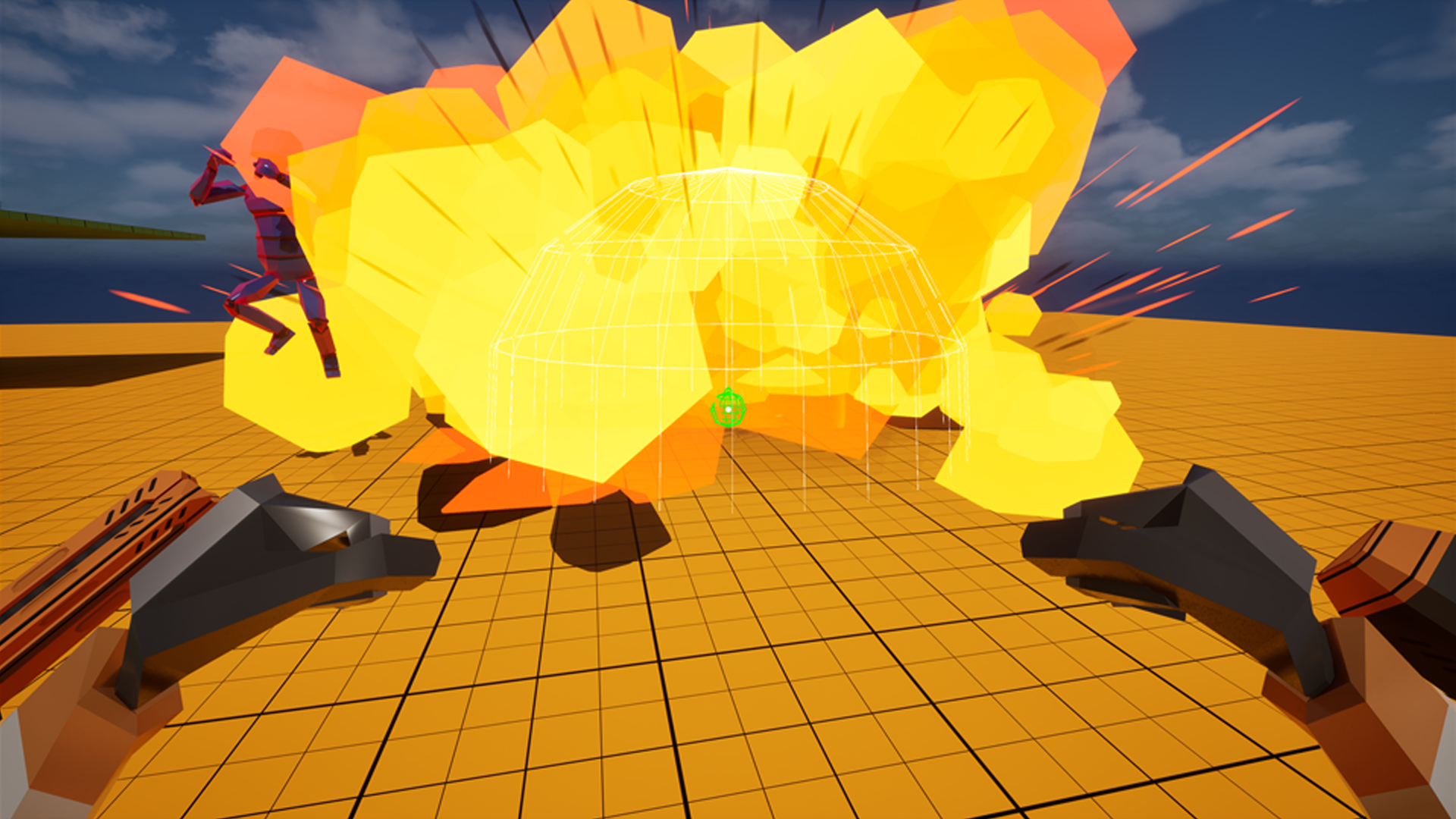

Upon detonating, AreaGameplayEffect is applied to all valid targets (actors that both have line-of-sight and pass Filter) within the AreaRadius. The AreaOffset vector can be used to adjust where the center of the radius will be, relative to the Collision collider (e.g. if the collider is at the tip of the projectile, but we want the AOE effect to originate at its center).

The bSkipAreaEffectForImpactTarget variable can be set to ignore the target of ImpactGameplayEffect when applying the AOE effect, if we want an AOE projectile to apply a different effect to any targets it hits directly.

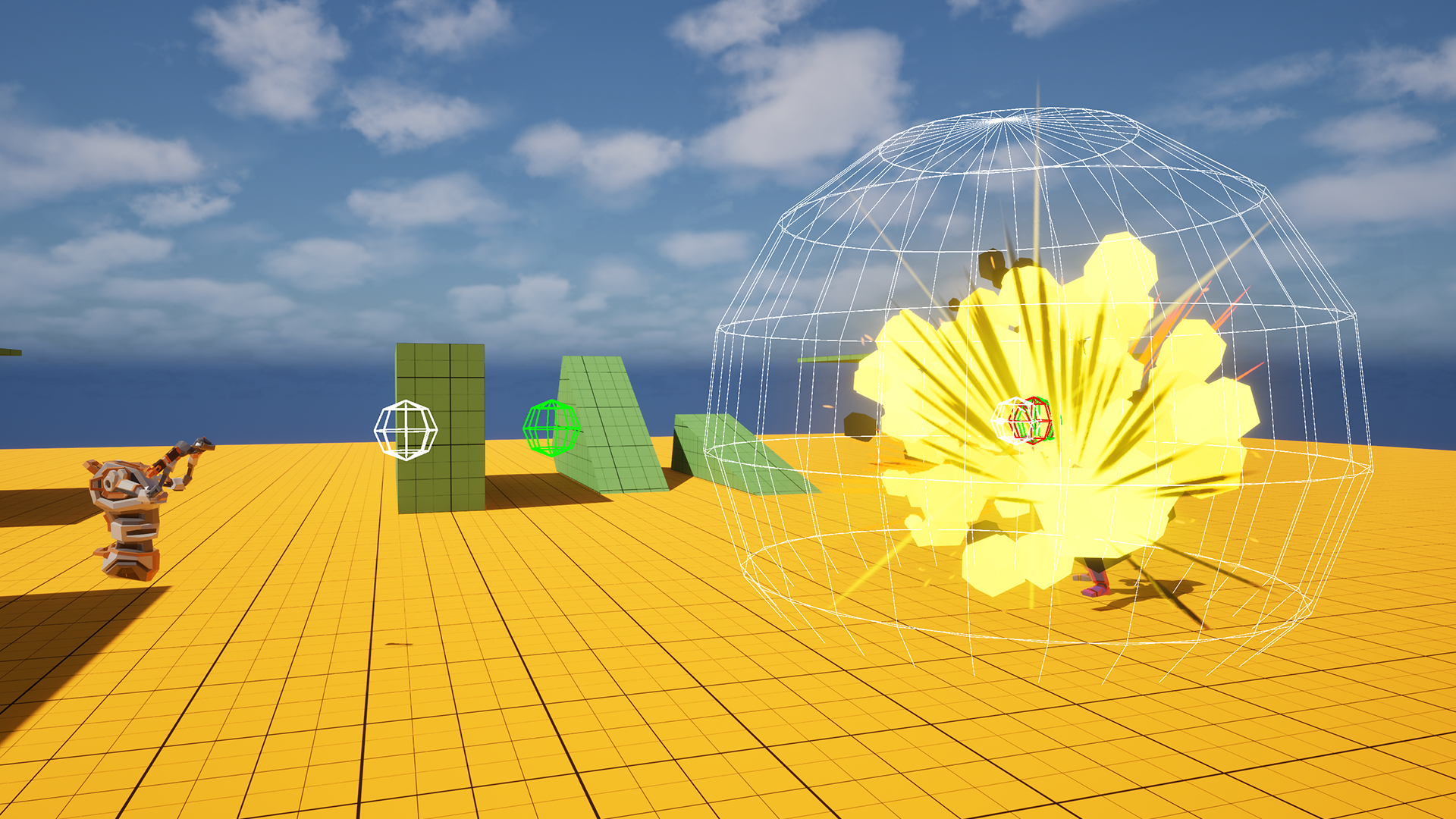

The exact radius of a projectile’s area of effect can be visualized by enabling the bDrawFinalPosition debug setting:

FX

There are four different events that can trigger FX: a detonation, a direct impact, a missed impact, and a bounce (i.e. when a bouncing projectile ricochets off a surface without detonating).

Both the “detonation” event and the “impact” events are triggered when a projectile detonates, so most projectiles only use one of these events. For example, a rocket may only use the “detonation” event to trigger explosion FX, while a spear may only use the “impact” events to trigger appropriate “hit” or “miss” FX.

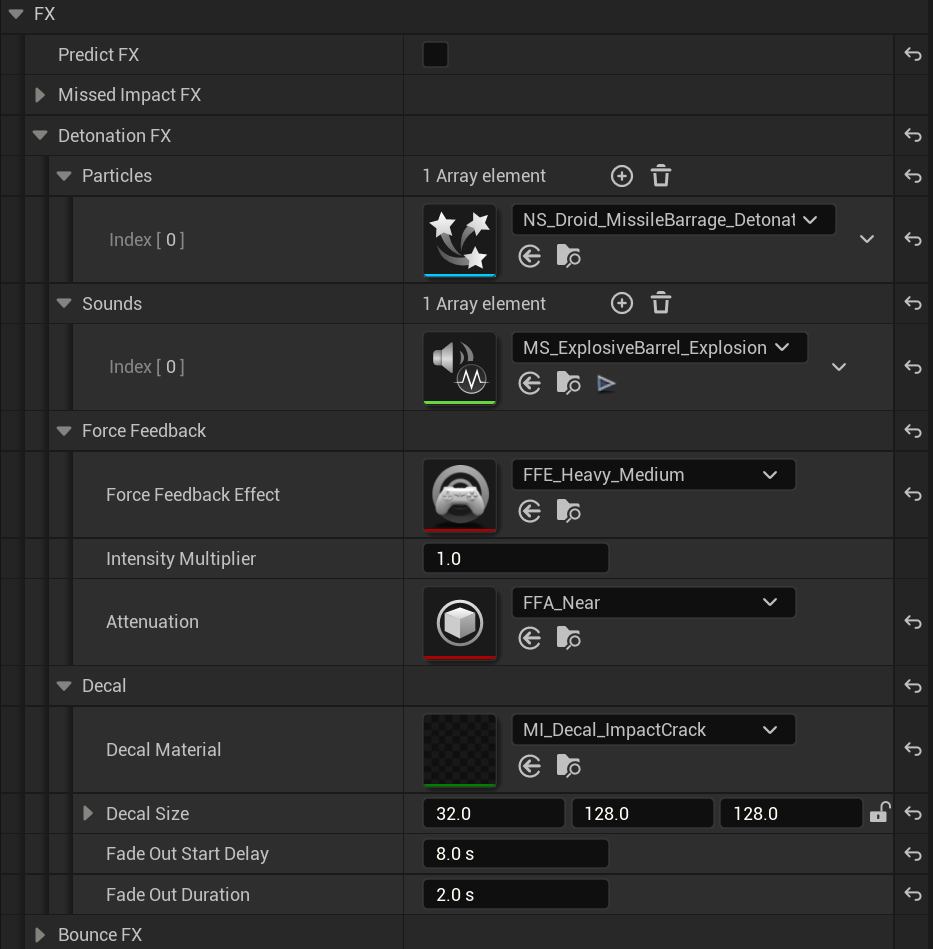

Each of these events can trigger a collection of particle effects, sound cues, force feedback, and decals, configurable in the archetype of each projectile class.

To compartmentalize these effects, we define a custom struct called FProjectileFX. This represents a collection of FX that can be triggered as a group. Projectiles have an instance of this struct defined for each of the aforementioned events, which will be collectively triggered when the event occurs:

This struct is not used, however, for FX triggered by the “direct impact” event. This event triggers the ImpactGameplayEffect, so we instead add a gameplay cue to this gameplay effect and put any FX we want inside that cue, to help improve compartmentalization.

Predicting FX

Because projectiles simulate their movement locally on each machine, the detonation, impact, and bounce events are triggered locally, and thus “predicted,” since we don’t wait for them to occur on the authoritative projectile.

This feels and looks great for small, fast, or inconsequential (e.g. no AOE or lingering effects) projectiles, like small bullets. Missed predictions and corrections are extremely rare and barely noticeable. But for larger or slower projectiles with big AOE effects, like a rocket, the risk of missed predictions increases, and correcting those predictions looks a lot more jarring, like having to resimulate an entire explosion in the correct location:

To fix this, projectiles have an option called bPredictFX. If bPredictFX is enabled, detonation and impact FX will be predicted (with plenty of reconciliation to correct any missed predictions that occur). If bPredictFX is disabled, these events will only be triggered by the authoritative projectile, and will be replicated to other machines when they occur.

Bounce FX are always predicted, since it’s not as important for these FX to always be accurate.

It’s up to the discretion of designers whether a projectile should predict its FX. Usually, we want smaller, quick, direct-hit projectiles, like bullets, to predict FX, while big, slow, AOE projectiles, like rockets, shouldn’t:

Regardless of bPredictFX, we never predict gameplay effects. And since we use a gameplay cue tied to the ImpactGameplayEffect for “direct impact” FX, this means these FX are never predicted. This is intentional, since we want our damage (which we also don’t predict), hitmarker, FX, and reaction animations to be synced together, and because hit-impact missed predictions are really irritating for players. From what I’ve seen, this is a fairly conventional approach in games: predicting FX except for ones that indicate damage (blood splatters, star particles, etc.).

Missed Prediction Reconciliation

As mentioned before, a projectile’s “detonation” is the single most important event of a projectile’s lifetime, and it’s crucial that this event is executed correctly on all machines.

To make sure of this, there are a number of potential missed predictions we account for on the owning client.

Premature Detonation

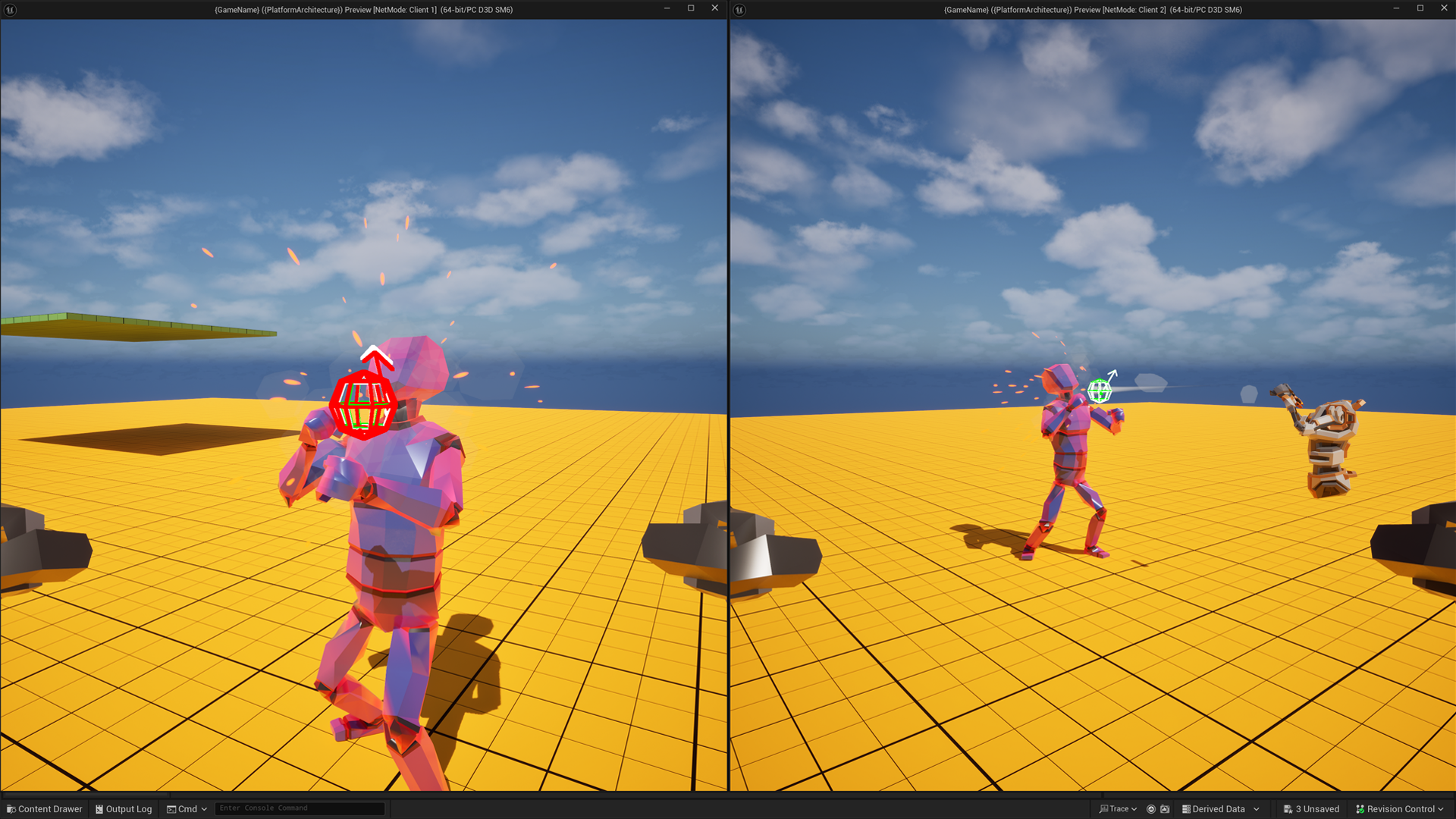

Since we’re simulating our projectile’s movement locally (as opposed to replicating movement), having two projectiles that aren’t perfectly synchronized can cause them to hit different targets. For example, when the fake projectile is ahead of the real one (since it’s fired first), if an enemy moves through the path of the projectile, they may be in the path of the projectile when the fake projectile reaches them, but not be in the path when the real projectile catches up. This would result in the fake projectile hitting the enemy, but the real one missing them:

On the client (right), playing with 200ms of ping, the fake projectile hits the enemy and detonates. But on the server (left), it misses and continues traveling. Because bPredictFX is disabled (we typically wouldn’t predict FX for a rocket projectile), we don’t even see an explosion from the fake projectile, since it’s waiting for the authoritative projectile’s detonation; it just disappears. If bPredictFX were enabled, we’d see an explosion where the fake projectile (mistakenly) detonated.

To detect this, after the fake projectile detonates, we set a short timer (determined by ping) called SwitchToAuthTimer. If the corresponding authoritative projectile hasn’t detonated when the timer ends, that means the fake projectile detonated prematurely.

To reconcile the misprediction, we immediately destroy the fake projectile and switch to the authoritative projectile: we make the replicated authoritative projectile visible on the owning client, and use it for all visuals going forward.

We can see the projectile disappear when it mistakenly detonates on the client. But once the timer ends, the projectile re-appears and continues traveling. This new projectile is the authoritative projectile being unhidden after the fake projectile has been destroyed. Once the authoritative projectile lands, the FX are played the correct location.

If bPredictFX was enabled, the fake projectile would have already played its FX in the incorrect location, meaning we’d end up seeing the FX played twice. This is a little annoying, but this misprediction occurs so rarely and only at such high latencies that it’s a fair tradeoff for an otherwise responsive and reliable system.

Late Detonation

For the same reason as the previous case, it’s possible for the authoritative projectile to hit something that the fake projectile missed. For example, if an enemy moves into the path of the projectile after the fake projectile has passed, but before the real projectile has caught up:

This time, the fake projectile misses the enemy and keeps traveling, but the authoritative projectile hits the enemy and detonates (which we see, since bPredictFX is disabled, meaning we use the authoritative projectile’s FX).

To detect this, when the authoritative projectile detonates, we simply check whether the fake projectile has also detonated. If it hasn’t, the fake projectile likely missed whatever the real projectile hit.

To reconcile this case, we do the same thing as before: destroy the fake projectile and switch to the real one:

Now, we destroy the fake projectile when the real one detonates, so it doesn’t keep traveling. (The red sphere shows where it was when it was destroyed.)

Since the projectile should detonate at this point, we’re not really “switching” to the authoritative projectile. Rather, we’re just using its detonation effects—which we do anyway if bPredictFX is disabled, which is why the FX look the same in the above example.

Note that when this occurs, it isn’t necessarily a missed prediction. It’s possible that the fake projectile may have just been about to detonate, but ended up slightly behind the authoritative projectile. This can happen if our ping estimates are slightly off, causing us to fast-forward the authoritative projectile too far, causing it to end up ahead of the fake one.

Regardless, in this situation, swapping out the fake projectile for the real one is harmless, so this doesn’t pose an issue. This only occurs when the projectile detonates, and detonation effects triggered by the fake and authoritative projectile are always be identical (since they’ll be in the same location, as per the next case), so there won’t be any visual discrepancies.

Inaccurate Detonation

Just because the fake and authoritative projectile detonate around the same time doesn’t mean they detonated at the same location. At high latencies, in particular, it’s possible that both projectiles detonated within an acceptable timespan, but did so in different locations.

For example, if the authoritative projectile missed the fake projectile’s target, but hit something directly behind it, the mistake wouldn’t be caught, since the authoritative projectile may still have detonated before SwitchToAuthTimer ended:

For this example, we’re using a projectile with bPredictFX enabled, since this is issue really hard to notice when FX aren’t predicted.

Here, the client’s fake projectile hits the moving platform. The authoritative projectile misses it, but hits the wall behind it before SwitchToAuthTimer ends. Because SwitchToAuthTimer is based on the client’s ping (since that determines how far ahead their fake projectile can be, and thus how long we should wait for the authoritative projectile to catch up), SwitchToAuthTimer may end up being fairly long, which increases the risk of this misprediction.

To account for this, once the authoritative projectile detonates, if the fake projectile has also detonated, we check to see where it detonated. If the two projectiles detonated a considerable distance apart, then the fake projectile likely hit the wrong target, and we once again destroy the fake projectile, and use the authoritative projectile’s effects:

This time, since we’re predicting the fake projectile’s FX, we end up playing our FX twice: once when the fake projectile mistakenly detonates, and once when the authoritative projectile performs the correct detonation. But, again, this is so rare that we’re okay with it; we just want to make sure the player sees what their projectile really hit.

And if the fake projectile hasn’t detonated yet, this will be caught by the previous case, which does the same thing: destroy the fake projectile and use the authoritative projectile’s effects.

Lost Projectile

Finally, it’s possible for either the fake or the authoritative projectile to lose their reference to the other. And without a reference to the other projectile, it becomes impossible to check for missed predictions.

This can happen if the fake projectile detonated so prematurely that it was destroyed by the time the authoritative projectile detonated (since projectiles usually destroy themselves after detonating), or if the authoritative projectile detonated so early (likely on spawn) that it hasn’t even been linked yet.

Fortunately, the former case is already handled by the Premature Detonation detection method: destruction is always deferred until SwitchToAuthTimer has had enough time to finish. When the authoritative projectile eventually detonates, we’ll have already switched to it, and we’ll just replay the detonation effects in the correct location.

The latter situation, however, we do have to account for, and we do that by deferring the detonation event. The replicated authoritative projectile is linked to its corresponding fake projectile on spawn, in BeginPlay. So, if we attempt to call Detonate before the projectile has been fully spawned (i.e. before BeginPlay), we won’t execute it. Instead, we’ll wait until BeginPlay is called (to ensure our projectiles get linked), and then try to detonate it again.

This is deferment is handled via the TornOff event. This function is called when a projectile detonates on the server, is propagated to clients, and will always be called after BeginPlay (since there needs to have been enough time for an initial replication tick). If we call Detonate too early, we wait until we receive the TornOff event, and then try to detonate again, since we’re guaranteed to have called BeginPlay at that point.

This second detonation should always succeed, and will either be a successful prediction (if the fake projectile, which has now been linked, has already detonated in the same location) or a missed prediction that will be caught by one of the above reconciliation methods, since our projectiles are now guaranteed to have been linked.

Remote Clients

Detonation

On remote clients (the clients that didn’t fire the projectile), the replicated authoritative projectile also simulates its movement and hit detection locally. To mitigate any synchronization issues this may cause, we use the TornOff event. When the server’s projectile detonates and tears off, the TornOff event is propagated to clients, which forces them to detonate if they haven’t done so already.

This is similar to firing a DetonateIfNotDetonated RPC, but we choose to use the tear-off framework instead because of replication timing; TornOff will always be called after BeginPlay and the actor’s initial replication update, which makes accounting for edge cases easier, since we can guarantee the order of events.

When the server’s projectile is torn off, it sends a final movement replication update (mentioned in the Movement section), which ensures the projectile detonates in the correct location on clients.

The server’s projectile will also send clients a collection of information specifying how the detonation occurred (e.g. the direction of the hit), in the form of a struct called DetonationInfo. If a client’s projectile hasn’t detonated yet and must be detonated by TornOff, DetonationInfo will be used to fill the detonation’s parameters, since it won’t have reliable data locally.

Rewinding

Due to the time it takes to replicate from the server and because of fast-forwarding, projectiles on remote clients will often appear a noticeable distance ahead of where they spawned—or, if the projectile detonates too quickly, not at all:

We saw this discrepancy earlier when looking at debugging options.

To fix this, when a projectile is first replicated to a remote client, we rewind it back to its spawn transform. This is done in BeginPlay, by simply teleporting the projectile backwards using a replicated property called SpawnTransform. By doing this, we ensure that remote clients see the entire trajectory and lifetime of the projectile:

When the projectile’s detonation is propagated to the client, we need to make sure it’s had enough time to catch up to the location of the detonation. To do this, in DetonationInfo’s OnRep function, we set a short timer called FinishedResimulationTimer, depending on how far the projectile is from the detonation location. Once that timer ends, the projectile will be detonated with DetonationInfo.

We do this in the OnRep instead of TornOff because DetonationInfo is set as soon as the server’s projectile detonates, but TornOff is often delayed to make sure there’s been enough time to send an initial replication update, which messes with our timing.

We actually put our aforementioned reconciliation code in this OnRep too—not in the TornOff function. So, really, the actual TornOff function is only used as a last resort, if the projectile somehow hasn’t replicated DetonationInfo by the time it’s finally torn off.

Resimulation

Lastly, we want to account for when a projectile detonates so quickly that it never appears on remote clients.

This isn’t a technical issue (we already account for projectiles that detonate too quickly, as detailed in the Lost Projectile section), but more a quality-of-life one. The projectile is detonating properly; we just never see it, since it’s detonating right when it spawns:

To fix this, we define a value called MinLifetime, which defines the minimum amount of time that we want a projectile to be visible for.

In DetonationInfo’s OnRep, when we’d normally detonate the projectile, we check to see how long the projectile has been alive for.

If the projectile hasn’t even finished spawning (meaning it hasn’t even been rewound yet), we teleport it back to its spawn transform and slow its velocity, such that it will take MinLifetime to reach the detonation location. (We also set a flag to prevent BeginPlay from rewinding it again when it’s eventually called.)

If the projectile has finished spawning, but hasn’t been alive for MinLifetime, we’ll just slow its velocity such that by the time it reaches the detonation location (since it’s still catching up due to being rewound), it will have been alive for MinLifetime.

Finally, if the projectile has been alive for at least MinLifetime, we’ll execute the detonation as usual.

Conclusion

Well, with all of those components broken down, that brings this section—and this series—to a close. Let’s take one final look at the difference projectile prediction makes (just to convince you that all of this isn’t completely worthless):

When I went to implement projectile prediction for my game, I had an impossible time finding any remotely relevant resources on the topic. This solution came from looking at open-source projects (like Unreal Tournament), using network limiters to reverse-engineer various games, scrubbing through netcode GDC talks for any mention of projectiles, and—more than anything else—a lot of trial-and-error.

I went through the effort of writing this lengthy series just because I wanted to put some kind of resource out there to help those trying to implement projectile prediction, since it’s such a common feature.

So, I really hope some of this was useful, and I hope it caused your experience with projectile prediction and network programming to be a little less blind and helpless than mine was.